Homograph

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the English language and the Chinese language and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2018) |

A homograph (from the Greek: ὁμός, homós 'same' and γράφω, gráphō 'write') is a word that shares the same written form as another word but has a different meaning.[1] However, some dictionaries insist that the words must also be pronounced differently,[2] while the Oxford English Dictionary says that the words should also be of "different origin".[3] In this vein, The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography lists various types of homographs, including those in which the words are discriminated by being in a different word class, such as hit, the verb to strike, and hit, the noun a strike.[4]

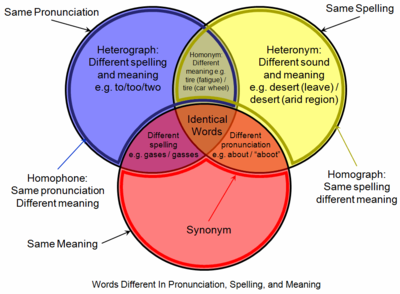

If, when spoken, the meanings may be distinguished by different pronunciations, the words are also heteronyms. Words with the same writing and pronunciation (i.e. are both homographs and homophones) are considered homonyms. However, in a broader sense the term "homonym" may be applied to words with the same writing or pronunciation. Homograph disambiguation is critically important in speech synthesis, natural language processing and other fields. Identically written different senses of what is judged to be fundamentally the same word are called polysemes; for example, wood (substance) and wood (area covered with trees).

In English

[edit]Examples:

- sow (verb) /soʊ/ – to plant seed

- sow (noun) /saʊ/ – female pig

where the words are heteronyms, spelt identically but pronounced differently. Here confusion is not possible in spoken language but could occur in written language.

- bear (verb) – to support or carry

- bear (noun) – the animal

where the words are homonyms, identical in spelling and pronunciation (/bɛər/), but different in meaning and grammatical function.

The above examples are of etymologically unrelated words. Some homographs are also etymological doublets, meaning they come from the same source and are spelt the same way in Modern English, but their distinct meanings are tied to their distinct pronunciations:

- Dominican /dəˈmɪnɪkən/ – of the Dominican Order or the Dominican Republic (fully anglicized, based on the Latin pronunciation of Dominicus [dɔˈmɪnɪkʊs], named for Saint Dominic)

- Dominican /ˌdɒmɪˈniːkən/ – of Dominica (slightly modified from the Spanish pronunciation of Dominica [ðomiˈnika], named for Latin diēs Dominica [ˈdjjɛːs dɔˈmɪnɪka] meaning "the Lord's Day" or "Sunday")

Both words ultimately come from Latin dominicus [dɔˈmɪnɪkʊs] meaning "of the Lord."

- violist /ˈvaɪəlɪst/ – viol player

- violist /viˈoʊlɪst/ – viola player

Both viol and viola come from Latin vitula.

More examples

[edit]| Word | Example of first meaning | Example of second meaning |

|---|---|---|

| lead | Gold is denser than lead /lɛd/. | The mother duck will lead /liːd/ her ducklings around. |

| close | "Will you please close /kloʊz/ that door!" | The tiger was now so close /kloʊs/ that I could smell it... |

| wind | The wind /wɪnd/ howled through the woodlands. | Wind /waɪnd/ your watch. |

| minute | I will be there in a minute /ˈmɪnɪt/. | That is a very minute /maɪˈnuːt///maɪˈnjuːt/ amount. |

In Chinese

[edit]Many Chinese varieties have homographs, called 多音字 (pinyin: duōyīnzì) or 重形字 (pinyin: chóngxíngzì), 破音字 (pinyin: pòyīnzì).

Old Chinese

[edit]Modern study of Old Chinese has found patterns that suggest a system of affixes.[5] One pattern is the addition of the prefix /*ɦ/, which turns transitive verbs into intransitive or passives in some cases:[6]

| Word | Pronunciationa | Meaninga | Pronunciationb | Meaningb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 見[7] | *kens | see | *ɦkens | appear |

| 敗[8] | *prats | defeat | *ɦprats | be defeated |

| All data from Baxter, 1992.[6] | ||||

Another pattern is the use of a /*s/ suffix, which seems to create nouns from verbs or verbs from nouns:[6]

| Word | Pronunciationa | Meaninga | Pronunciationb | Meaningb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 傳 | *dron | transmit | *drons | (n.) record |

| 磨 | *maj | grind | *majs | grindstone |

| 塞 | *sɨk | (v.) block | *sɨks | border, frontier |

| 衣 | *ʔjɨj | clothing | *ʔjɨjs | wear, clothe |

| 王 | *wjaŋ | king | *wjaŋs | be king |

| All data from Baxter, 1992.[6] | ||||

Middle Chinese

[edit]Many homographs in Old Chinese also exist in Middle Chinese. Examples of homographs in Middle Chinese are:

| Word | Pronunciationa | Meaninga | Pronunciationb | Meaningb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 易 | /jĭe꜄/ | easy | /jĭɛk꜆/ | (v.) change |

| 別 | /bĭɛt꜆/ | (v.) part | /pĭɛt꜆/ | differentiate, other |

| 上 | /꜂ʑĭaŋ/ | rise, give | /ʑĭaŋ꜄/ | above, top, emperor |

| 長 | /꜀dʲʱĭaŋ/ | long | /꜂tʲĭaŋ/ | lengthen, elder |

| Reconstructed phonology from Wang Li on the tables in the article Middle Chinese. Tone names in terms of level (꜀平), rising (꜂上), departing (去꜄), and entering (入꜆) are given. All meanings and their respective pronunciations from Wang et al., 2000.[9] | ||||

Modern Chinese

[edit]Many homographs in Old Chinese and Middle Chinese also exist in modern Chinese varieties. Homographs which did not exist in Old Chinese or Middle Chinese often come into existence due to differences between literary and colloquial readings of Chinese characters. Other homographs may have been created due to merging two different characters into the same glyph during script reform (See Simplified Chinese characters and Shinjitai).

Some examples of homographs in Cantonese from Middle Chinese are:

| Word | Pronunciationa | Meaninga | Pronunciationb | Meaningb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 易 | [jiː˨] | easy | [jɪk˨] | (v.) change |

| 上 | [ɕœːŋ˩˧] | rise, give | [ɕœːŋ˨] | above, top, emperor |

| 長 | [tɕʰœːŋ˨˩] | long | [tɕœːŋ˧˥] | lengthen, elder |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "One of two or more words that have the same spelling but differ in origin, meaning, and sometimes pronunciation, such as fair (pleasing in appearance) and fair (market) or wind (wĭnd) and wind (wīnd)".

- ^ Homophones and Homographs: An American Dictionary, 4th ed., McFarland, 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: homograph.

- ^ Atkins, BTS.; Rundell, M., The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography, OUP Oxford, 2008, pp. 192 - 193.

- ^ Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-22809-1.

- ^ a b c d Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs). Berlin and New York: de Gruyter Mouton. pp. 218–220. ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- ^ The two meanings were later distinguished through the means of radicals, so that 見 ('to see', Std. Mand. jiàn) was unchanged, while 見 ('to appear', Std. Mand. xiàn) came to be written as 現.

- ^ This distinction was preserved in Middle Chinese using voiced and unvoiced initials. Thus, 敗 (transitive, 'to defeat') was read as 北邁切 (Baxter, paejH), while 敗 (intransitive, 'to collapse; be defeated') was read as 薄邁切 (Baxter, baejH). 《增韻》:凡物不自敗而敗之,則北邁切。物自毀壞,則薄邁切。Modern Wu dialects (e.g., Shanghainese, Suzhounese), which preserve the three-way Middle Chinese contrast between voiced/aspirated/unaspirated initials, do not appear to preserve this distinction.

- ^ Wang Li; et al. (2000). 王力古漢語字典. Beijing: 中華書局. ISBN 7-101-01219-1.