Dachau concentration camp

48°16′08″N 11°28′07″E / 48.26889°N 11.46861°E

| Dachau | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

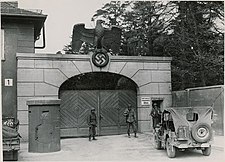

U.S. soldiers guarding the main entrance to Dachau just after liberation, 1945 | |

| Other names | German: Konzentrationslager (KZ) Dachau, IPA: [ˈdaxaʊ] |

| Location | Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany |

| Built by | Nazi Germany |

| Operated by | Schutzstaffel (SS) |

| Commandant | List of commandants |

| Original use | Political prison |

| Operational | March 1933 – April 1945 |

| Inmates | Political prisoners, Poles, Romani, Jews, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, Catholic priests, Communists[1] |

| Number of inmates | Over 188,000 (estimated)[2] |

| Killed | 41,500 (per Dachau website) |

| Liberated by | U.S. Army |

| Website | kz-gedenkstaette-dachau |

Dachau (UK: /ˈdæxaʊ/, /-kaʊ/; US: /ˈdɑːxaʊ/, /-kaʊ/)[3][4] was one of the first[a] concentration camps built by Nazi Germany and the longest-running one, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents, which consisted of communists, social democrats, and other dissidents.[6] It is located on the grounds of an abandoned munitions factory northeast of the medieval town of Dachau, about 16 km (10 mi) northwest of Munich in the state of Bavaria, in southern Germany.[7] After its opening by Heinrich Himmler, its purpose was enlarged to include forced labor, and eventually, the imprisonment of Jews, Romani, German and Austrian criminals, and, finally, foreign nationals from countries that Germany occupied or invaded. The Dachau camp system grew to include nearly 100 sub-camps, which were mostly work camps or Arbeitskommandos, and were located throughout southern Germany and Austria.[8] The main camp was liberated by U.S. forces on 29 April 1945.

Prisoners lived in constant fear of brutal treatment and terror detention including standing cells, floggings, the so-called tree or pole hanging, and standing at attention for extremely long periods.[9] There were 32,000 documented deaths at the camp, and thousands that are undocumented.[10] Approximately 10,000 of the 30,000 prisoners were sick at the time of liberation.[11][12]

In the postwar years, the Dachau facility served to hold SS soldiers awaiting trial. After 1948, it held ethnic Germans who had been expelled from eastern Europe and were awaiting resettlement, and also was used for a time as a United States military base during the occupation. It was finally closed in 1960.

There are several religious memorials within the Memorial Site,[13] which is open to the public.[14]

General overview

This overview section duplicates the intended purpose of the article's lead section, which should provide an overview of the subject. (June 2022) |

Dachau served as a prototype and model for the other German concentration camps that followed. Almost every community in Germany had members taken away to these camps. Newspapers continually reported "the removal of the enemies of the Reich to concentration camps." As early as 1935, a jingle went around: "Lieber Herr Gott, mach mich stumm, dass ich nicht nach Dachau komm'" ("Dear Lord God, make me dumb [silent], That I may not to Dachau come").[15]

The camp's layout and building plans were developed by Commandant Theodor Eicke and were applied to all later camps. He had a separate, secure camp near the command center, which consisted of living quarters, administration and army camps. Eicke became the chief inspector for all concentration camps, responsible for organizing others according to his model.[16]

The Dachau complex included the prisoners' camp which occupied approximately 5 acres, and the much larger area of SS training school including barracks, factories plus other facilities of around 20 acres.[17]

The entrance gate used by prisoners carries the phrase "Arbeit macht frei" (lit. '"Work makes free"', or "Work makes [one] free"; contextual English translation: "Work shall set you free"). This phrase was also used in several other concentration camps such as Theresienstadt,[18] near Prague, and Auschwitz I.

Dachau was the concentration camp that was in operation the longest, from March 1933 to April 1945, nearly all twelve years of the Nazi regime. Dachau's close proximity to Munich, where Hitler came to power and where the Nazi Party had its official headquarters, made Dachau a convenient location. From 1933 to 1938, the prisoners were mainly German nationals detained for political reasons. After the Reichspogromnacht or Kristallnacht, 30,000 male Jewish citizens were deported to concentration camps. More than 10,000 of them were interned in Dachau alone. As the German military occupied other European states, citizens from across Europe were sent to concentration camps. Subsequently, the camp was used for prisoners of all sorts, from every nation occupied by the forces of the Third Reich.[19]: 137

In the postwar years, the camp continued in use. From 1945 through 1948, the camp was used by the Allies as a prison for SS officers awaiting trial. After 1948, when hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were expelled from eastern Europe, it held Germans from Czechoslovakia until they could be resettled. It also served as a military base for the United States, which maintained forces in the country. It was closed in 1960. At the insistence of survivors, various memorials have been constructed and installed here.[19]: 138

Demographic statistics vary but they are in the same general range. One source gives a general estimate of over 200,000 prisoners from more than 30 countries during Nazi rule, of whom two-thirds were political prisoners, including many Catholic priests, and nearly one-third were Jews. At least 25,613 prisoners are believed to have been murdered in the camp and almost another 10,000 in its subcamps,[20] primarily from disease, malnutrition and suicide. In late 1944, a typhus epidemic occurred in the camp caused by poor sanitation and overcrowding, which caused more than 15,000 deaths.[21] It was followed by an evacuation, in which large numbers of the prisoners died. Toward the end of the war, death marches to and from the camp caused the deaths of numerous unrecorded prisoners. After liberation, prisoners weakened beyond recovery by the starvation conditions continued to die.[22] Two thousand cases of "the dread black typhus" had already been identified by 3 May, and the U.S. Seventh Army was "working day and night to alleviate the appalling conditions at the camp".[23] Prisoners with typhus, a louse-borne disease with an incubation period from 12 to 18 days, were treated by the 116th Evacuation Hospital, while the 127th would be the general hospital for the other illnesses. There were 227 documented deaths among the 2,252 patients cared for by the 127th.[22]

Over the 12 years of use as a concentration camp, the Dachau administration recorded the intake of 206,206 prisoners and deaths of 31,951. Crematoria were constructed to dispose of the deceased. Visitors may now walk through the buildings and view the ovens used to cremate bodies, which hid the evidence of many deaths. It is claimed that in 1942, more than 3,166 prisoners in weakened condition were transported to Hartheim Castle near Linz, and were executed by poison gas because they were deemed unfit.[19]: 137 [25]

Between January and April 1945 11,560 detainees died at KZ Dachau according to a U.S. Army report of 1945,[26] though the Dachau administration registered 12,596 deaths from typhus at the camp over the same period.[21]

Dachau was the third concentration camp to be liberated by British or American Allied forces.[27]

History

Establishment

After the takeover of Bavaria on 9 March 1933, Heinrich Himmler, then Chief of Police in Munich, began to speak with the administration of an unused gunpowder and munitions factory. He toured the site to see if it could be used for quartering protective-custody prisoners. The concentration camp at Dachau was opened 22 March 1933, with the arrival of about 200 prisoners from Stadelheim Prison in Munich and the Landsberg fortress (where Hitler had written Mein Kampf during his imprisonment).[28] Himmler announced in the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten newspaper that the camp could hold up to 5,000 people, and described it as "the first concentration camp for political prisoners" to be used to restore calm to Germany.[29] It became the first regular concentration camp established by the coalition government of the National Socialist German Worker's Party (Nazi Party) and the German National People's Party (dissolved on 6 July 1933).

Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals and emigrants were sent to Dachau after the 1935 passage of the Nuremberg Laws which institutionalized racial discrimination.[30] In early 1937, the SS, using prisoner labor, initiated construction of a large complex capable of holding 6,000 prisoners. The construction was officially completed in mid-August 1938.[16] More political opponents, and over 11,000 German and Austrian Jews were sent to the camp after the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland in 1938. Sinti and Roma in the hundreds were sent to the camp in 1939, and over 13,000 prisoners were sent to the camp from Poland in 1940.[30][31] Representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross inspected the camp in 1935 and 1938 and documented the harsh conditions.[32]

First deaths 1933: Investigation

Shortly after the SS was commissioned to supplement the Bavarian police overseeing the Dachau camp, the first reports of prisoner deaths at Dachau began to emerge. In April 1933, Josef Hartinger, an official from the Bavarian Justice Ministry and physician Moritz Flamm, part-time medical examiner, arrived at the camp to investigate the deaths in accordance with the Bavarian penal code.[33] They noted many inconsistencies between the injuries on the corpses and the camp guards' accounts of the deaths. Over a number of months, Hartinger and Flamm uncovered clear evidence of murder and compiled a dossier of charges against Hilmar Wäckerle, the SS commandant of Dachau, Werner Nürnbergk, the camp doctor, and Josef Mutzbauer, the camp's chief administrator (Kanzleiobersekretär). In June 1933, Hartinger presented the case to his superior, Bavarian State Prosecutor Karl Wintersberger. Initially supportive of the investigation, Wintersberger became reluctant to submit the resulting indictment to the Justice Ministry, increasingly under the influence of the SS. Hartinger reduced the scope of the dossier to the four clearest cases and Wintersberger signed it, after first notifying Himmler as a courtesy. The killings at Dachau suddenly stopped (temporarily), Wäckerle was transferred to Stuttgart and replaced by Theodor Eicke. The indictment and related evidence reached the office of Hans Frank, the Bavarian Justice Minister, but was intercepted by Gauleiter Adolf Wagner and locked away in a desk only to be discovered by the US Army.[34] In 1934, both Hartinger and Wintersberger were transferred to provincial positions. Flamm was no longer employed as a medical examiner and was to survive two attempts on his life before his suspicious death in the same year. Flamm's thoroughly gathered and documented evidence within Hartiger's indictment ensured that it achieved convictions of senior Nazis at the Nuremberg trials in 1947. Wintersberger's complicit behaviour is documented in his own evidence to the Pohl Trial.[35]

Forced labor

The prisoners of Dachau concentration camp originally were to serve as forced labor for a munition factory, and to expand the camp. It was used as a training center for the SS-Totenkopfverbände guards and was a model for other concentration camps.[36] The camp was about 300 m × 600 m (1,000 ft × 2,000 ft) in rectangular shape. The prisoners' entrance was secured by an iron gate with the motto "Arbeit macht frei" ("Work will make you free"). This reflected Nazi propaganda, which had concentration camps as labor and re-education camps. This was their original purpose, but the focus was soon shifted to using forced labor as a method of torture and murder.[37] The original slogan was left on the gates.

As of 1938, the procedure for new arrivals occurred at the Schubraum, where prisoners were to hand over their clothing and possessions.[38]: 61 One former Luxembourgish prisoner, Albert Theis, reflected about the room, "There we were stripped of all our clothes. Everything had to be handed over: money, rings, watches. One was now stark naked".[39]

The camp included an administration building that contained offices for the Gestapo trial commissioner, SS authorities, the camp leader and his deputies. These administration offices consisted of large storage rooms for the personal belongings of prisoners, the bunker, roll-call square where guards would also inflict punishment on prisoners (especially those who tried to escape), the canteen where prisoners served SS men with cigarettes and food, the museum containing plaster images of prisoners who suffered from bodily defects, the camp office, the library, the barracks, and the infirmary, which was staffed by prisoners who had previously held occupations such as physicians or army surgeons.[40]

Operation Barbarossa

Over 4,000 Soviet prisoners of war were murdered by the Dachau commandant's guard at the SS shooting range located at Hebertshausen, two kilometers from the main camp, in the years 1941/1943.[41][42][43] These murders were a clear violation of the provisions laid down in the Geneva Convention for prisoners of war. The SS used the cynical term Sonderbehandlung ("special treatment") for these criminal executions. The first executions of the Soviet prisoners of war at the Hebertshausen shooting range took place on 25 November 1941.[44]

After 1942, the number of prisoners being held at the camp continued to exceed 12,000.[45] Dachau originally held communists, leading socialists and other "enemies of the state" in 1933 but, over time, the Nazis began to send German Jews to the camp. In the early years of imprisonment, Jews were offered permission to emigrate overseas if they "voluntarily" gave their property to enhance Hitler's public treasury.[45] Once Austria was annexed and Czechoslovakia was dissolved, the citizens of both countries became the next prisoners at Dachau. In 1940, Dachau became filled with Polish prisoners, who continued to be the majority of the prisoner population until Dachau was officially liberated.[46]

The prisoner enclosure at the camp was heavily guarded to ensure that no prisoners escaped. A 3-metre-wide (10 ft) no-man's land was the first marker of confinement for prisoners; an area which, upon entry, would elicit lethal gunfire from guard towers. Guards are known to have tossed inmates' caps into this area, resulting in the death of the prisoners when they attempted to retrieve the caps. Despondent prisoners committed suicide by entering the zone. A four-foot-deep and eight-foot-broad (1.2 × 2.4 m) creek, connected with the river Amper, lay on the west side between the "neutral-zone" and the electrically charged, and barbed wire fence which surrounded the entire prisoner enclosure.[47]

In August 1944 a women's camp opened inside Dachau. In the last months of the war, the conditions at Dachau deteriorated. As Allied forces advanced toward Germany, the Germans began to move prisoners from concentration camps near the front to more centrally located camps. They hoped to prevent the liberation of large numbers of prisoners. Transports from the evacuated camps arrived continuously at Dachau. After days of travel with little or no food or water, the prisoners arrived weak and exhausted, often near death. Typhus epidemics became a serious problem as a result of overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, insufficient provisions, and the weakened state of the prisoners.[citation needed]

Owing to repeated transports from the front, the camp was constantly overcrowded and the hygiene conditions were beneath human dignity. Starting from the end of 1944 up to the day of liberation, 15,000 people died, about half of all the prisoners held at KZ Dachau. Five hundred Soviet POWs were executed by firing squad. The first shipment of women came from Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Final days

As late as 19 April 1945, prisoners were sent to KZ Dachau; on that date a freight train from Buchenwald with nearly 4,500 was diverted to Nammering. SS troops and police confiscated food and water that local townspeople tried to give to the prisoners. Nearly three hundred dead bodies were ordered removed from the train and carried to a ravine over 400 metres (1⁄4 mi) away. The 524 prisoners who had been forced to carry the dead to this site were then shot by the guards, and buried along with those who had died on the train. Nearly 800 bodies went into this mass grave. The train continued on to KZ Dachau.[48]

During April 1945 as U.S. troops drove deeper into Bavaria, the commander of KZ Dachau suggested to Himmler that the camp be turned over to the Allies. Himmler, in signed correspondence, prohibited such a move, adding that "No prisoners shall be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy alive."[49]

On 24 April 1945, just days before the U.S. troops arrived at the camp, the commandant and a strong guard forced between 6,000 and 7,000 surviving inmates on a death march from Dachau south to Eurasburg, then eastwards towards the Tegernsee; liberated two days after Hitler's death by a Nisei-ethnicity U.S. Army artillery battalion.[50] Any prisoners who could not keep up on the six-day march were shot. Many others died of exhaustion, hunger and exposure.[51] Months later a mass grave containing 1,071 prisoners was found along the route.[52][53]

Though at the time of liberation the death rate had peaked at 200 per day, after the liberation by U.S. forces the rate eventually fell to between 50 and 80 deaths per day from malnutrition and disease. In addition to the direct abuse of the SS and the harsh conditions, people died from typhus epidemics and starvation. The number of inmates had peaked in 1944 with transports from evacuated camps in the east (such as Auschwitz), and the resulting overcrowding led to an increase in the death rate.[54]

Main camp

Purpose

Dachau was opened in March 1933.[7] The press statement given at the opening stated:

On Wednesday the first concentration camp is to be opened in Dachau with an accommodation for 5000 people. 'All Communists and—where necessary—Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated here, as in the long run it is not possible to keep individual functionaries in the state prisons without overburdening these prisons, and on the other hand these people cannot be released because attempts have shown that they persist in their efforts to agitate and organize as soon as they are released.[55]

Whatever the publicly stated purpose of the camp, the SS men who arrived there on 11 May 1933 were left in no illusion as to its real purpose by the speech given on that day by Johann-Erasmus Freiherr von Malsen-Ponickau[56]

Comrades of the SS!

You all know what the Fuehrer has called us to do. We have not come here for human encounters with those pigs in there. We do not consider them human beings, as we are, but as second-class people. For years they have been able to continue their criminal existence. But now we are in power. If those pigs had come to power, they would have cut off all our heads. Therefore we have no room for sentimentalism. If anyone here cannot bear to see the blood of comrades, he does not belong and had better leave. The more of these pig dogs we strike down, the fewer we need to feed.

Between the years 1933 and 1945, more than 3.5 million Germans were imprisoned in such concentration camps or prison for political reasons.[57][58][59] Approximately 77,000 Germans were killed for one or another form of resistance by Special Courts, courts-martial, and the civil justice system. Many of these Germans had served in government, the military, or in civil positions, which were considered to enable them to engage in subversion and conspiracy against the Nazis.[60]

Organization

The camp was divided into two sections: the camp area and the crematorium. The camp area consisted of 32 barracks, including one for clergy imprisoned for opposing the Nazi regime and one reserved for medical experiments. The courtyard between the prison and the central kitchen was used for the summary execution of prisoners. The camp was surrounded by an electrified barbed-wire fence, a ditch, and a wall with seven guard towers.[16]

In early 1937, the SS, using prisoner labor, initiated construction of a large complex of buildings on the grounds of the original camp. The construction was officially completed in mid-August 1938 and the camp remained essentially unchanged and in operation until 1945. A crematorium that was next to, but not directly accessible from within the camp, was erected in 1942. KZ Dachau was therefore the longest running concentration camp of the Third Reich. The Dachau complex included other SS facilities beside the concentration camp—a leader school of the economic and civil service, the medical school of the SS, etc. The camp at that time was called a "protective custody camp," and occupied less than half of the area of the entire complex.[16]

Medical experimentation

Hundreds of prisoners suffered and died, or were executed, in medical experiments conducted at KZ Dachau, of which Sigmund Rascher was in charge. Hypothermia experiments involved exposure to vats of icy water or being strapped down naked outdoors in freezing temperatures. Attempts at reviving the subjects included scalding baths, and forcing naked women to have sexual intercourse with the unconscious victim. Nearly 100 prisoners died during these experiments.[61] The original records of the experiments were destroyed "in an attempt to conceal the atrocities".[b][62]

Extensive communication between the investigators and Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, documents the experiments.[63]

During 1942, "high altitude" experiments were conducted. Victims were subjected to rapid decompression to pressures found at 4,300 metres (14,100 ft), and experienced spasmodic convulsions, agonal breathing, and eventual death.[64]

Demographics

The camp was originally designed for holding German and Austrian political prisoners and Jews, but in 1935 it began to be used also for ordinary criminals. Inside the camp there was a sharp division between the two groups of prisoners; those who were there for political reasons and therefore wore a red tag, and the criminals, who wore a green tag.[54] The political prisoners who were there because they disagreed with Nazi Party policies, or with Hitler, naturally did not consider themselves criminals. Dachau was used as the chief camp for Christian (mainly Catholic)[65] clergy who were imprisoned for not conforming with the Nazi Party line.[citation needed]

During the war, other nationals were transferred to it, including French; in 1940 Poles; in 1941 people from the Balkans, Czechs, Yugoslavs; and in 1942, Russians.[54]

Prisoners were divided into categories. At first, they were classified by the nature of the crime for which they were accused, but eventually were classified by the specific authority-type under whose command a person was sent to camp.[66]: 53 Political prisoners who had been arrested by the Gestapo wore a red badge, "professional" criminals sent by the Criminal Courts wore a green badge, Cri-Po prisoners arrested by the criminal police wore a brown badge, "work-shy and asocial" people sent by the welfare authorities or the Gestapo wore a black badge, Jehovah's Witnesses arrested by the Gestapo wore a violet badge, homosexuals sent by the criminal courts wore a pink badge, emigrants arrested by the Gestapo wore a blue badge, "race polluters" arrested by the criminal court or Gestapo wore badges with a black outline, second-termers arrested by the Gestapo wore a bar matching the color of their badge, "idiots" wore a white armband with the label Blöd (Stupid), Romani wore a black triangle, and Jews, whose incarceration in the Dachau concentration camp dramatically increased after Kristallnacht, wore a yellow badge, combined with another color.[66]: 54–69

The average number of Germans in the camp during the war was 3,000. Just before the liberation many German prisoners were evacuated, but 2,000 of these Germans died during the evacuation transport. Evacuated prisoners included such prominent political and religious figures as Martin Niemöller, Kurt von Schuschnigg, Édouard Daladier, Léon Blum, Franz Halder, and Hjalmar Schacht.[54]

Clergy

In an effort to counter the strength and influence of spiritual resistance, Nazi security services monitored clergy very closely.[67]: 141–142 Priests were frequently denounced, arrested and sent to concentration camps, often simply on the basis of being "suspected of activities hostile to the State" or that there was reason to "suppose that his dealings might harm society".[67]: 142 Despite SS hostility to religious observance, the Vatican and German bishops successfully lobbied the regime to concentrate clergy at one camp and obtained permission to build a chapel, for the priests to live communally and for time to be allotted to them for their religious and intellectual activity. Priests Barracks at Dachau were established in Blocks 26, 28 and 30, though only temporarily. 26 became the international block and 28 was reserved for Poles—the most numerous group.[67]: 145–6

Of a total of 2,720 clergy recorded as imprisoned at Dachau,[65] the overwhelming majority, some 2,579 (or 94.88%) were Catholic. Among the other denominations, there were 109 Protestants, 22 Greek Orthodox, 8 Old Catholics and Mariavites and 2 Muslims. In his Dachau: The Official History 1933–1945, Paul Berben noted that R. Schnabel's 1966 investigation, Die Frommen in der Hölle ("The Pious Ones in Hell") found an alternative total of 2,771 and included the fate all the clergy listed, with 692 noted as deceased and 336 sent out on "invalid trainloads" and therefore presumed dead.[67]: 276–277 Over 400 German priests were sent to Dachau.[68] Total numbers incarcerated are nonetheless difficult to assert, for some clergy were not recognised as such by the camp authorities, and some—particularly Poles—did not wish to be identified as such, fearing they would be mistreated.[67]: 157

The Nazis introduced a racial hierarchy—keeping Poles in harsh conditions, while favoring German priests.[67]: 148 697 Poles arrived in December 1941, and a further 500 of mainly elderly clergy arrived in October the following year. Inadequately clothed for the bitter cold, of this group, only 82 survived. A large number of Polish priests were chosen for Nazi medical experiments. In November 1942, 20 were given phlegmons.[how?] 120 were used by Dr Schilling for malaria experiments between July 1942 and May 1944. Several Poles met their deaths with the "invalid trains" sent out from the camp, others were liquidated in the camp and given bogus death certificates. Some died of cruel punishment for misdemeanors—beaten to death or run to exhaustion.[67]: 148–9

Staff

The camp staff consisted mostly of male SS, although 19 female guards served at Dachau as well, most of them until liberation.[69] Sixteen have been identified including Fanny Baur, Leopoldine Bittermann, Ernestine Brenner, Anna Buck, Rosa Dolaschko, Maria Eder, Rosa Grassmann, Betty Hanneschaleger, Ruth Elfriede Hildner, Josefa Keller, Berta Kimplinger, Lieselotte Klaudat, Theresia Kopp, Rosalie Leimboeck, and Thea Miesl.[70] Female guards were also assigned to the Augsburg Michelwerke, Burgau, Kaufering, Mühldorf, and Munich Agfa Camera Werke subcamps. In mid-April 1945, female subcamps at Kaufering, Augsburg, and Munich were closed, and the SS stationed the women at Dachau. Several Norwegians worked as guards at the Dachau camp.[71]

In the major Dachau war crimes case (United States of America v. Martin Gottfried Weiss et.al.), forty-two officials of Dachau were tried from November to December 1945. All were found guilty—thirty-six of the defendants were sentenced to death on 13 December 1945, of whom 23 were hanged on 28–29 May 1946, including the commandant, SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Gottfried Weiss, SS-Obersturmführer Freidrich Wilhelm Ruppert and camp doctors Karl Schilling and Fritz Hintermeyer. Camp commandant Weiss admitted in affidavit testimony that most of the deaths at Dachau during his administration were due to "typhus, TB, dysentery, pneumonia, pleurisy, and body weakness brought about by lack of food." His testimony also admitted to deaths by shootings, hangings and medical experiments.[72][73][74] Ruppert ordered and supervised the deaths of innumerable prisoners at Dachau main and subcamps, according to the War Crimes Commission official trial transcript. He testified about hangings, shootings and lethal injections, but did not admit to direct responsibility for any individual deaths.[75] An anonymous Dutch prisoner contended that British Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent Noor Inayat Khan was cruelly beaten by SS officer Wilhelm Ruppert before being shot from behind; the beating may have been the actual cause of her death.[76]

Satellite camps and sub-camps

Satellite camps under the authority of Dachau were established in the summer and autumn of 1944 near armaments factories throughout southern Germany to increase war production. Dachau alone had more than 30 large subcamps, and hundreds of smaller ones,[77] in which over 30,000 prisoners worked almost exclusively on armaments.[78]

Overall, the Dachau concentration camp system included 123 sub-camps and Kommandos which were set up in 1943 when factories were built near the main camp to make use of forced labor of the Dachau prisoners. Out of the 123 sub-camps, eleven of them were called Kaufering, distinguished by a number at the end of each. All Kaufering sub-camps were set up to specifically build three underground factories (Allied bombing raids made it necessary for them to be underground) for a project called Ringeltaube (wood pigeon), which planned to be the location in which the German jet fighter plane, Messerschmitt Me 262, was to be built. In the last days of war, in April 1945, the Kaufering camps were evacuated and around 15,000 prisoners were sent up to the main Dachau camp. Typhus alone was estimated to have caused 15,000 deaths between December 1944 and April 1945.[79][80] "Within the first month after the arrival of the American troops, 10,000 prisoners were treated for malnutrition and kindred diseases. In spite of this one hundred prisoners died each day during the first month from typhus, dysentery or general weakness".[73]

As U.S. Army troops neared the Dachau sub-camp at Landsberg on 27 April 1945, the SS officer in charge ordered that 4,000 prisoners be murdered. Windows and doors of their huts were nailed shut. The buildings were then doused with gasoline and set afire. Prisoners who were naked or nearly so were burned to death, while some managed to crawl out of the buildings before dying. Earlier that day, as Wehrmacht troops withdrew from Landsberg am Lech, townspeople hung white sheets from their windows. Infuriated SS troops dragged German civilians from their homes and hanged them from trees.[81][82]

Liberation

Main camp

As the Allies began to advance on Nazi Germany, the SS began to evacuate the first concentration camps in summer 1944.[38] Thousands of prisoners were killed before the evacuation due to being ill or unable to walk. At the end of 1944, the overcrowding of camps began to take its toll on the prisoners. The unhygienic conditions and the supplies of food rations became disastrous. In November a typhus fever epidemic broke out that took thousands of lives.[38]

In the second phase of the evacuation, in April 1945, Himmler gave direct evacuation routes for remaining camps. Prisoners who were from the northern part of Germany were to be directed to the Baltic and North Sea coasts to be drowned. The prisoners from the southern part were to be gathered in the Alps, which was the location in which the SS wanted to resist the Allies.[38] On 28 April 1945, an armed revolt took place in the town of Dachau. Both former and escaped concentration camp prisoners and a renegade Volkssturm (civilian militia) company took part. At about 8:30 am the rebels occupied the Town Hall. The SS gruesomely suppressed the revolt within a few hours.[38]

Being fully aware that Germany was about to be defeated in World War II, the SS invested its time in removing evidence of the crimes it committed in the concentration camps. They began destroying incriminating evidence in April 1945 and planned on murdering the prisoners using codenames "Wolke A-I" (Cloud A-1) and "Wolkenbrand" (Cloud fire).[83] However, these plans were not carried out. In mid-April, plans to evacuate the camp started by sending prisoners toward Tyrol. On 26 April, over 10,000 prisoners were forced to leave the Dachau concentration camp on foot, in trains, or in trucks. The largest group of some 7,000 prisoners was driven southward on a foot-march lasting several days. More than 1,000 prisoners did not survive this march. The evacuation transports cost many thousands of prisoners their lives.[38]

On 26 April 1945 prisoner Karl Riemer fled the Dachau concentration camp to get help from American troops and on 28 April Victor Maurer, a representative of the International Red Cross, negotiated an agreement to surrender the camp to U.S. troops. That night a secretly formed International Prisoners Committee took over the control of the camp. Units of 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Felix L. Sparks, were ordered to secure the camp. On 29 April Sparks led part of his battalion as they entered the camp over a side wall.[84] At about the same time, Brigadier General Henning Linden led the 222nd Infantry Regiment of the 42nd (Rainbow) Infantry Division soldiers including his aide, Lieutenant William Cowling,[85] to accept the formal surrender of the camp from German Lieutenant Heinrich Wicker at an entrance between the camp and the compound for the SS garrison. Linden was traveling with Marguerite Higgins and other reporters; as a result, Linden's detachment generated international headlines by accepting the surrender of the camp. More than 30,000 Jews and political prisoners were freed, and since 1945 adherents of the 42nd and 45th Division versions of events have argued over which unit was the first to liberate Dachau.[38]: 201 [86]: 283 [87][88][89]

Satellite camps liberation

The first Dachau subcamp discovered by advancing Allied forces was Kaufering IV by the 12th Armored Division on 27 April 1945.[90][91] Subcamps liberated by the 12th Armored Division included: Erpting, Schrobenhausen, Schwabing, Langerringen, Türkheim, Lauingen, Schwabach, Germering.[92]

During the liberation of the sub-camps surrounding Dachau, advance scouts of the U.S. Army's 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, a segregated battalion consisting of Nisei, 2nd generation Japanese-Americans, liberated the 3,000 prisoners of the "Kaufering IV Hurlach"[93] slave labor camp.[94] Perisco describes an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) team (code name LUXE) leading Army Intelligence to a "Camp IV" on 29 April. "They found the camp afire and a stack of some four hundred bodies burning ... American soldiers then went into Landsberg and rounded up all the male civilians they could find and marched them out to the camp. The former commandant was forced to lie amidst a pile of corpses. The male population of Landsberg was then ordered to walk by, and ordered to spit on the commandant as they passed. The commandant was then turned over to a group of liberated camp survivors".[95] The 522nd's personnel later discovered the survivors of a death march[96] headed generally southwards from the Dachau main camp to Eurasburg, then eastwards towards the Austrian border on 2 May, just west of the town of Waakirchen.[97][98]

Weather at the time of liberation was unseasonably cool and temperatures trended down through the first two days of May; on 2 May, the area received a snowstorm with 10 centimetres (4 in) of snow at nearby Munich.[99] Proper clothing was still scarce and film footage from the time (as seen in The World at War) shows naked, gaunt people either wandering on snow or dead under it.

Due to the number of sub-camps over a large area that comprised the Dachau concentration camp complex, many Allied units have been officially recognized by the United States Army Center of Military History and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as liberating units of Dachau, including: the 4th Infantry Division, 36th Infantry Division, 42nd Infantry Division, 45th Infantry Division, 63rd Infantry Division, 99th Infantry Division, 103rd Infantry Division, 10th Armored Division, 12th Armored Division, 14th Armored Division, 20th Armored Division, and the 101st Airborne Division.[100]

Killing of camp guards

American troops killed some of the camp guards after they had surrendered. The number is disputed, as some were killed in combat, some while attempting to surrender, and others after their surrender was accepted. In 1989, Brigadier General Felix L. Sparks, the Colonel in command of a battalion that was present, stated:

The total number of German guards killed at Dachau during that day most certainly does not exceed fifty, with thirty probably being a more accurate figure. The regimental records of the 157th Field Artillery Regiment for that date indicate that over a thousand German prisoners were brought to the regimental collecting point. Since my task force was leading the regimental attack, almost all the prisoners were taken by the task force, including several hundred from Dachau.[101]

An Inspector General report resulting from a US Army investigation conducted between 3 and 8 May 1945—titled "American Army Investigation of Alleged Mistreatment of German Guards at Dachau"—found that 21 plus "a number" of presumed SS men were killed, with others being wounded after their surrender had been accepted.[102][103] In addition, 25 to 50 SS guards were estimated to have been killed by the liberated prisoners.[104] Lee Miller visited the camp just after liberation, and photographed several guards who were killed by soldiers or prisoners.[105]

According to Sparks, court-martial charges were drawn up against him and several other men under his command, but General George S. Patton, who had recently been appointed military governor of Bavaria, chose to dismiss the charges.[101]

Colonel Charles L. Decker, an acting deputy judge advocate, concluded in late 1945 that, while war crimes had been committed at Dachau by Germany, "Certainly, there was no such systematic criminality among United States forces as pervaded the Nazi groups in Germany."[106]

American troops also forced local citizens to the camp to see for themselves the conditions there and to help bury the dead.[91] Many local residents were shocked about the experience and claimed no knowledge of the activities at the camp.[86]: 292

Post-liberation Easter

6 May 1945 (23 April on the Orthodox calendar) was the day of Pascha, Orthodox Easter. In a cell block used by Catholic priests to say daily Mass, several Greek, Serbian and Russian priests and one Serbian deacon, wearing makeshift vestments made from towels of the SS guard, gathered with several hundred Greek, Serbian and Russian prisoners to celebrate the Paschal Vigil. A prisoner named Rahr described the scene:[107]

In the entire history of the Orthodox Church there has probably never been an Easter service like the one at Dachau in 1945. Greek and Serbian priests together with a Serbian deacon adorned the makeshift 'vestments' over their blue and gray-striped prisoners' uniforms. Then they began to chant, changing from Greek to Slavic, and then back again to Greek. The Easter Canon, the Easter Sticheras—everything was recited from memory. The Gospel—In the beginning was the Word—also from memory. And finally, the Homily of Saint John—also from memory. A young Greek monk from the Holy Mountain stood up in front of us and recited it with such infectious enthusiasm that we shall never forget him as long as we live. Saint John Chrysostomos himself seemed to speak through him to us and to the rest of the world as well!

There is a Russian Orthodox chapel at the camp today, and it is well known for its icon of Christ leading the prisoners out of the camp gates.[d]

After liberation

Authorities worked night and day to alleviate conditions at the camp immediately following the liberation as an epidemic of black typhus swept through the prisoner population. Two thousand cases had already been reported by 3 May.[108]

By October 1945, the former camp was being used by the U.S. Army as a place of confinement for war criminals, the SS and important witnesses.[109] It was also the site of the Dachau Trials for German war criminals, a site chosen for its symbolism. In 1948, the Bavarian government established housing for refugees on the site, and this remained for many years.[110] Among those held in the Dachau internment camp set up under the U.S. Army were Elsa Ehrich, Maria Mandl, and Elisabeth Ruppert.[111]

The Kaserne quarters and other buildings used by the guards and trainee guards were converted and served as the Eastman Barracks, an American military post.[citation needed] After the closure of the Eastman Barracks in 1974, these areas are now occupied by the Bavarian Bereitschaftspolizei (rapid response police unit).[112]

Deportation of Soviet nationals

By January 1946, 18,000 members of the SS were being confined at the camp along with an additional 12,000 persons, including deserters from the Russian army and a number who had been captured in German Army uniform. The occupants of two barracks rioted as 271 of the Russian deserters were to be loaded onto trains that would return them to Russian-controlled lands, as agreed at the Yalta Conference. Inmates barricaded themselves inside two barracks. While the first was able to be cleared without too much trouble, those in the second building set fire to it, tore off their clothing in an effort to frustrate the guards, and linked arms to resist being removed from the building.[113] Tear gas was used by the American soldiers before rushing the barracks, only for them to find that many had killed themselves.[114] The American services newspaper Stars and Stripes reported:

“The GIs quickly cut down most of those who had hanged themselves from the rafters. Those still conscious were screaming in Russian, pointing first at the guns of the guards, then at themselves, begging to us to shoot.”[114]

Ten of the soldiers killed themselves during the riot while another 21 attempted suicide, apparently with razor blades. Many had "cracked heads" inflicted by 500 American guards, in the attempt to bring the situation under control. One of those injured later died in a hospital. The New York Times reported on the death with the headline, "Russian Traitor Dies of Wounds".[115]

List of personnel

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2019) |

Commandants

- SS-Standartenführer Hilmar Wäckerle (22 March 1933 – 26 June 1933)

- SS-Gruppenführer Theodor Eicke (26 June 1933 – 4 July 1934)

- SS-Oberführer Alexander Reiner (4 July 1934 – 22 October 1934)

- SS-Brigadeführer Berthold Maack (22 October 1934 – 12 January 1935)

- SS-Oberführer Heinrich Deubel (12 January 1935 – 31 March 1936)

- SS-Oberführer Hans Loritz (31 March 1936 – 7 January 1939)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Alexander Piorkowski (7 January 1939 – 2 January 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Weiß (3 January 1942 – 30 September 1943)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Eduard Weiter (30 September 1943 – 26 April 1945)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Weiß (26 April 1945 – 28 April 1945)

Other staff

- Adolf Eichmann (29 January 1934 – October 1934)[116]

- Rudolf Höss (1934–1938)[117]

- Max Kögel (1937–1938)

- SS-Untersturmführer Hans Steinbrenner (1905–1964), brutal guard who greeted new arrivals with his improvized "Welcome Ceremony".

- SS-Obergruppenführer Gerhard Freiherr von Almey, half-brother of Ludolf von Alvensleben. Executed in 1955, in Moscow.

- Johannes Heesters[118] (visited the camp and entertained the SS officers, was also given/giving tours)[119]

- Otto Rahn (1937)[120]

- SS-Untersturmführer Johannes Otto

- SS-Untersturmführer Heinrich Wicker, killed in the Dachau liberation reprisals

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Johann Kantschuster was the arrest commandant in Dachau (1933–1939), went on to become camp commandant at Fort Breendonk, Belgium

- SS-Sturmbannführer Robert Erspenmüller, first warden of the guards and right-hand of Hilmar Wäckerle. Disagreed with Eicke and was transferred away.

SS and civilian doctors

- Dr. Werner Nuernbergk – First camp doctor, escaped charges for falsifying death certificates in 1933

- SS-Untersturmführer Dr. Hans Eisele – (13 March 1912 – 3 May 1967) – Sentenced to death, but reprieved and released in 1952. Fled to Egypt after new accusations in 1958.[121]

- SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Fritz Hintermayer – (28 Oct 1911 – 29 May 1946) – Executed by the Allies

- Dr. Ernst Holzlöhner – (23 February 1899 – 14 June 1945) – Committed suicide

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Fridolin Karl Puhr – (30 April 1913 – 31 May 1957) – Sentenced to death, later commuted to 10-years imprisonment

- SS-Untersturmführer Dr. Sigmund Rascher – (12 February 1909 – 26 April 1945) – Executed by the SS

- Dr. Claus Schilling – (25 July 1871 – 28 May 1946) – Executed by the Allies

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Horst Schumann – (11 May 1906 – 5 May 1983) – Escaped to Ghana, later extradited to West Germany

- SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Helmuth Vetter – (21 March 1910 – 2 February 1949) – Executed by the Allies

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Wilhelm Witteler – (20 April 1909 – 13 May 1993) – Sentenced to death, later commuted to 20-years imprisonment

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Waldemar Wolter – (19 May 1908 – 28 May 1947) – Executed by the Allies

Memorial

Between 1945 and 1948 when the camp was handed over to the Bavarian authorities, many accused war criminals and members of the SS were imprisoned at the camp. Owing to the severe refugee crisis mainly caused by the expulsions of ethnic Germans, the camp was used from late 1948 to house 2000 Germans from Czechoslovakia (mainly from the Sudetenland). This settlement was called Dachau-East and remained until the mid-1960s.[122] During this time, former prisoners banded together to erect a memorial on the site of the camp. The display, which was reworked in 2003, follows the path of new arrivals to the camp. Two of the barracks have been rebuilt and one shows a cross-section of the entire history of the camp since the original barracks had to be torn down due to their poor condition when the memorial was built. The other 30 barracks are indicated by low cement curbs filled with pebbles.[123]

In media

- In his 2013 autobiography, Moose: Chapters from My Life, in the chapter entitled, "Dachau", author Robert B. Sherman chronicles his experiences as an American Army serviceman during the initial hours of Dachau's liberation.[124]

- In Lewis Black's first book, Nothing's Sacred, he mentions visiting the camp as part of his tour of Europe and how it looked all cleaned up and spiffy, "like some delightful holiday camp", and only the crematorium building showed any sign of the horror that went on there.

- In Maus, Vladek describes his time interned at Dachau, among his time at other concentration camps. He describes the journey to Dachau in over-crowded trains, trading rations for other goods and favors to stay alive, and contracting typhus.

- Frontline: "Memory of the Camps" (7 May 1985, Season 3, Episode 18), is a 56-minute television documentary that addresses Dachau and other Nazi concentration camps[125][126]

See also

Notes

- ^ Nohra concentration camp, which opened 19 days earlier, was the first, but it was not purpose built and only existed for a few months.[5]

- ^ "In an attempt to conceal the atrocities, the original, incriminating records of most of the concentration camp studies of humans were destroyed before the camps were captured by the Allied forces." (See Medicine, Ethics, and the Third Reich: Historical and Contemporary Issues p. 88)

- ^ The caption for the photograph in the U.S. National Archives reads, "SC208765, Soldiers of the 42nd Infantry Division, U.S. Seventh Army, order SS men to come forward when one of their number tried to escape from the Dachau, Germany, concentration camp after it was captured by U.S. forces. Men on the ground in background feign death by falling as the guards fired a volley at the fleeing SS men. (157th Regt. 4/29/45)."

- ^ The U.S. 7th Army's version of the events of the Dachau Liberation is available in Report of Operations of the Seventh United States Army, Vol. 3, p. 382.

References

- ^ "Dachau – 7th Army Official Report, May 1945". TankDestroyer.net. May 1945. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Holocaust Encyclopedia – Dachau". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Dachau". Webster's New World College Dictionary.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1, Pt. B: Early camps, youth camps, and concentration camps and subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA): Pt. B / vol. ed.: Geoffrey P. Megargee. Vol. 1. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ^ "Dachau". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Ein Konzentrationslager für politische Gefangene in der Nähe von Dachau". Münchner Neueste Nachrichten ("The Munich Latest News") (in German). The Holocaust History Project. 21 March 1933. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

The Munich Chief of Police, Himmler, has issued the following press announcement: On Wednesday the first concentration camp is to be opened in Dachau with an accommodation for 5000 persons. 'All Communists and—where necessary—Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated here, as in the long run it is not possible to keep individual functionaries in the state prisons without overburdening these prisons, and on the other hand these people cannot be released because attempts have shown that they persist in their efforts to agitate and organise as soon as they are released.'

- ^ Concentration Camp Dachau Entry Registers (Zugangsbuecher) 1933–1945. retrieved 13 November 2014

- ^ "Station 7: Courtyard and Bunker". Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Station 11: Crematorium". Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Investigation of alleged mistreatment of German guards at the Concentration Camp at Dachau, Germany, by elements of the XV Corps". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Headquarters Seventh Army Office of the Chief of Staff APO TSS, C/O Postmaster New York, NY 2 May 1945 Memorandum to: Inspector General, Seventh Army The Coming General directs that you conduct a formal investigation of alleged mistreatment of German guards at the Concentration Camp at Dachau, Germany, by elements of the XV Corps. A. White, Major General, G.S.C. Chief of Staff Testimony of: Capt. Richard F. Taylor 0-408680, Military Government, Detachment I-13, G-3". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Station 12: Religious Memorials". Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "1945 – present History of the Memorial Site – Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". www.kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Janowitz, Morris (September 1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". The American Journal of Sociology. 52 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 141–146. doi:10.1086/219961. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2770938. PMID 20994277. S2CID 44356394.

- ^ a b c d "Dachau". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2009.

- ^ The Liberator : One World War II Soldier's 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau. Alex Kershaw. 2012. Crown. New York. p. 270

- ^ "An archway at Theresienstadt bearing the phrase, "Arbeit Macht Frei." – Collections Search – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Edkins, Jenny (2003). Trauma and the memory of politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521534208.

- ^ Zámečník, Stanislav (2004). That Was Dachau 1933–1945. Translated by Paton, Derek B. Paris: Fondation internationale de Dachau; Cherche Midi. pp. 377, 379.

- ^ a b Zamecnick, Stanislas (2013). C'était ça, Dachau: 1933–1945 [This was Dachau: 1933–1945] (in French). Paris: Cherche midi. ISBN 978-2749132969., p. 71: 2,903 deaths from typhus in January 1945, 3,991 in February, 3,534 in March, 2,168 in April before the liberation. 14,511 registered typhus deaths since it began to spread in October 1944.

- ^ a b "University of Minnesota Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies. Hospitalization at Dachau". Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Typhus Epidemic Sweeping Camp. INS International News Service New Castle News, 3 May 1945 p. 1

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 11 January 2011

- ^ "Hartheim Euthanasia Center". Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "War Crimes and Punishment of War Crimes" (PDF). ETO. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Stone, Dan G.; Wood, Angela (2007). Holocaust: The events and their impact on real people, in conjunction with the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education (1st American ed.). New York. p. 144. ISBN 978-0756625351. OCLC 150893310.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marcuse, Harold. Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. p. 21

- ^ Neuhäusler (1960), What Was It Like..., p. 7

- ^ a b "Timeline 1933–1945: History of the Dachau Concentration Camp". KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Sinti & Roma: Victims of the Nazi Era, 1933–1945". A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Dromi, Shai M. (2020). Above the Fray: The Red Cross and the Making of the Humanitarian NGO Sector. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0226680385.

- ^ Ryback, Timothy W. Hitler’s First Victims: The Quest for Justice, Vintage, 2015. p. 17

- ^ United States. Office of Chief of Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis Criminality (1946). Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume 3. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ "1216-PS Concentration Camp Dachau: Special Orders (1933)". Harvard Law School Library Nuremberg Trials Project. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Dachau Liberated." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 27 March 2013.

- ^ "Station 2: Jourhouse – Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". Kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de. 29 April 1945. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. 2005.

- ^ "Station 5: Shunt Room – Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". Kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Neuhäusler (1960), What Was It Like..., pp. 9–11

- ^ "Redeveloping the commemorative site at the former SS shooting range Hebertshausen". Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". 1 November 2014.

- ^ "Commemorative Site at the former "SS Shooting Range Hebertshausen"". Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Memorial to the murdered Soviet soldiers (Hebertshausen)". 11 January 2014.

- ^ a b Neuhäusler (1960), What Was It like..., p. 13

- ^ Neuhäusler (1960), What Was It like..., p. 14

- ^ Neuhäusler (1960), What Was It like..., p. 11

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. A sign outside of the town of Nammering marks the site of a mass shooting by the SS. Retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ Maguire, Peter (2010). Law and War: International Law & American History. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0231146463.

- ^ "The 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and the Dachau Subcamps". Go For Broke NEC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Death Marches". The Holocaust: A Learning Site for Students. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ 1,071 More Dachau Dead Found. New York Times 18 August 1945. p. 5

- ^ Death march from Dachau and the liberation of the survivors (Motion picture). Content Media Group. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d 7th Army, U.S. (1945). Dachau. University of Wisconsin Digital Collection.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ein Konzentrationslager für politische Gefangene in der Nähe von Dachau" (PDF). Münchner Neueste Nachrichten ("The Munich Latest News") (in German). Ernst Klett Verlag. 21 March 1933. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Dillon, Christopher (2014). "5". In Wachsmann, Nikolaus; Steinbacher, Sybille (eds.). Gewaltakte der SS in der Frühphase des Konzentrationslagers Dachau: Situationsbedingt oder Rache? (in German). Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 978-3835326309.

- ^ Henry Maitles "Never again!: A review of David Goldhagen, [sic: read Daniel] 'Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust'" Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Socialist Review, further referenced to G. Almond, "The German Resistance Movement", Current History 10 (1946), pp. 409–527.

- ^ David Clay, Contending with Hitler: Varieties of German Resistance in the Third Reich, p. 122 (1994) ISBN 0521414598

- ^ Otis C. Mitchell, Hitler's Nazi State: The Years of Dictatorial Rule, 1934–1945 (1988), p. 217

- ^ Peter Hoffmann, The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945, p. xiii

- ^ "Holocaust on Trial The experiments by Peter Tyson". Nova OnLine WTTW11. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Robert L. Berger (1994). "Nazi Science-The Dachau Hypothermia Experiments". In John J. Michalczyk (ed.). Medicine, Ethics, and the Third Reich: Historical and Contemporary Issues. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 88. ISBN 978-1556127526. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "Nazi Science – The Dachau Hypothermia Experiments". Robert L. Berger, N Engl J Med 1990; 322:1435–1440 17 May 1990 doi:10.1056/NEJM199005173222006. quote: "On analysis, the Dachau hypothermia study has all the ingredients of a scientific fraud, and rejection of the data on purely scientific grounds is inevitable. They cannot advance science or save human lives." ... "Future citations are inappropriate on scientific grounds."

- ^ Andrew Korda (April 2006). "The Nazi medical experiments". Australian Defence Force. 7 (1). Australian ADF Health. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b Burger, John (14 June 2016). "Last Priest from Dachau Concentration Camp Dies at 102". Archived from the original on 15 June 2016.

- ^ a b Neurath, Paul Martin, Christian Fleck, and Nico Stehr. The Society of Terror: Inside the Dachau and Buchenwald Concentration Camps, Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berben, Paul (1975). Dachau: The Official History 1933–1945. London: Norfolk Press. ISBN 085211009X.

- ^ Ian Kershaw; The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation; 4th Edn; Oxford University Press; New York; 2000; pp. 210–11

- ^ Daniel Patrick Brown (2002), The Camp Women. The Female Auxiliaries who Assisted the SS in Running the Nazi Concentration Camp System, ISBN 0764314440.

- ^ Brown (2002), The Camp Women.

- ^ "Norske vakter jobbet i Hitlers konsentrasjonsleire" [Norwegian guards worked in Hitler's concentration camps] (in Norwegian). Vg nyheter. 15 November 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ US v. Weiss, pp. 16–19

- ^ a b UN War Crimes Commission, p. 6

- ^ Bloxham, Donald (2001). Genocide on Trial War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0191543357.

- ^ US v. Weiss, pp. 19–20

- ^ Shrabani, Basu (2008). Spy princess : the life of Noor Inayat Khan. Stroud: History. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-0750950565.

- ^ "Dachau subcamps" (PDF). Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte (House of Bavarian History). Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Dachau". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ US v. Weiss, p. 4

- ^ UN War Crimes Commission, p. 5

- ^ http://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1167593 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Retrieved 11 January 2014

- ^ Citizen Soldiers. Stephen Ambrose. 1997. pp. 463, 464. ISBN 0684815257

- ^ The Gestapo on trial : evidence from Nuremberg. Carruthers, Bob (The illustrated ed.). South Yorkshire, England. 29 January 2014. ISBN 978-1473849433. OCLC 903967032.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "45th Infantry Division.com". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ Cowan, Howard (Associated Press) (30 April 1945). "Notorious Nazi Prison Camp is Liberated, 32,000 are Freed". The Evening Times. Sayre, PA. p. 7.

- ^ a b Alex Kershaw, The Liberator: One World War II Soldier's 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau, 2012.

- ^ James Stuart Olson, Historical Dictionary of the 1950s, 2000, p. 125

- ^ Joe Wilson, The 761st "Black Panther" Tank Battalion in World War II, 1999, p. 185

- ^ Sam Dann, Dachau 29 April 1945: the Rainbow Liberation Memoirs, 1998, p. 6

- ^ "The 12th Armored Division". The Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Die Amerikanische Armee entdeckt den Holocaust (The American army discovered the Holocaust)". Europäische Holocaustgedenkstätte Stiftung (European Holocaust Memorial Foundation). Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Liberation of Concentration Camps". The 12th Armored Division Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ "Kaufering IV – Hurlach – Schwabmunchen". Kaufering.com. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Central Europe Campaign – 522nd Field Artillery Battalion". Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ Joseph E Persico (1979). Piercing the Reich. Viking Press. p. 306. ISBN 0670554901.

- ^ "Todesmärsche Dachau memorial website's map page of KZ-Dachau death march". Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ "Central Europe Campaign – 522nd Field Artillery Battalion". Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Search Results". www.ushmm.org.

- ^ http://kachelmannwetter.com/de/messwerte Kachelmann Weather archive

- ^ "U.S. Army Divisions Recognized as Liberating Units by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Center of Military". The Holocaust Encyclopedia – US Army Units. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ a b Albert Panebianco (ed). Dachau its liberation Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine 157th Infantry Association, Felix L. Sparks, Secretary 15 June 1989. (backup site Archived 24 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Testimony of: Lt. Howard E. Buchner, MC, 0-435481, 3rd Bn., 157th Infantry". Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ The Nuremberg Trials: International Criminal Law Since 1945 / Die Nürnberger ... By Lawrence Raful. 60th Anniversary International Conference / Internationale Konferenz zum 60. Jahrestag (Google eBook). p. 314

- ^ Zarusky, Jürgen (2002). "'That is not the American Way of Fighting:' The Shooting of Captured SS-Men During the Liberation of Dachau". In Wolfgang Benz; Barbara Distel (eds.). Dachau and the Nazi Terror 1933–1945. Vol. 2, Studies and Reports. Dachau: Verlag Dachauer Hefte. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-3980858717. Excerpt online

- ^ Burke, Carolyn (2005). Lee Miller: A Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 261. ISBN 978-0375401473.

- ^ "War Crimes and Punishment of War Crimes" (PDF). ETO. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Gleb Alexandrovitch Rahr – Prisoner R (Russian) – Pascha (Easter) in Dachau". Orthodoxytoday.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Typhus Epidemic Sweeping Camp". (INS) New Castle News 3 May 1945 p. 1

- ^ "Dachau Officials Will Face Trail – U.S. Army Will Open Hearings of Cases Against 40 to 50 Early Next Month". Wireless to the New York Times. New York Times 21 October 1945, p. 11

- ^ "Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site (pedagogical information)". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Prison for defendants; Landsberg hangings –Collections Search – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff (21 October 2002). "Neue Museumskonzepte für die Konzentrationslager". Welt Online (in German). Axel Springer AG. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

... die SS-Kasernen neben dem KZ Dachau wurden zuerst (bis 1974) von der US-Armee bezogen. Seither nutzt sie die VI. Bayerische Bereitschaftspolizei. (... the SS barracks adjacent to the Dachau concentration camp were at first occupied by the US Army (until 1974). Since then they have been used by the Sixth Rapid Response Unit of the Bavarian Police.)

- ^ McLaughlin, Kathleen (20 January 1946). "Soviet Deserters Suicides in Dachau – 10 Die, 21 Slash Themselves as Russians Who Fought with Nazis Defy Repatriation". New York Times. p. 25.

- ^ a b Jähner, Harald (2019). Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich 1945–1955 (Paperback). London: W H Allen. pp. 62, 63. ISBN 978-0753557877.

- ^ "Russian Traitor Dies of Wounds". The New York Times. 22 January 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "The Nizkor Project". transcript from the 1961 Eichmann trial. Shofar FTP archive and the Nizkor project. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ^ "The Trial of German Major War Criminals Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany 4th April to 15th April, 1946: One Hundred and Eighth Day: Monday, 15th April, 1946 (Part 1 of 10)". the Nizkor Project. 1991–2009. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Klee, Kulturlexikon, S. 227.

- ^ Klee, Kulturlexikon, S. 232.

- ^ Preston, John (21 May 2008). "The original Indiana Jones: Otto Rahn and the temple of doom". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ "Robert Fisk: Butcher of Buchenwald in an Egyptian paradise". The Independent. 7 August 2010.

- ^ Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001 Harold Marcuse

- ^ "Reshaping Dachau for Visitors, 1933–2000". marcuse.faculty.history.ucsb.edu.

- ^ Sherman, Robert B. "Dachau" in Moose: Chapters From My Life; AuthorHouse Publishers; Bloomington IN; 2013; ISBN 978-1491883662

- ^ "Memory of the Camps". IMDb. 1985.

- ^ "Memory of the Camps". TopDocumentaries.com. 1985.

Bibliography

- Bishop, Lt. Col. Leo V.; Glasgow, Maj. Frank J.; Fisher, Maj. George A., eds. (1946). The Fighting Forty-Fifth: the Combat Report of an Infantry Division. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.: 45th Infantry Division [Army & Navy Publishing Co.] OCLC 4249021.

- Buechner, Howard A. (1986). Dachau—The Hour of the Avenger. Thunderbird Press. ISBN 0913159042.

- Dillon, Christopher (2015). Dachau and the SS: A Schooling in Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199656523.

- Kozal, Czesli W. (2004). Memoir of Fr. Czesli W. (Chester) Kozal, O.M.I. Translated by Ischler, Paul. Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. OCLC 57253860.

- Marcuse, Harold (2001). Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521552042.

- Neuhäusler, Johann (1960). What Was It Like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?: An Attempt to Come Closer to the Truth. Munich: Manz A.G.

- Timothy W. Ryback (2015). Hitler's First Victims: The Quest for Justice. Vintage. ISBN 978-0804172004.

- Roberts, Donald R (2008). Heather R. Biola (ed.). The other war, a World War II journal. Elkins, WV: McClain Printing Co. ISBN 978-0870127755. Includes report written for: United States. Army. Infantry Division, 9th. Office of the Surgeon. Interrogation of SS Officers and Men at Dachau.

- Headquarters Third US Army and Eastern Military District, Office of the Judge Advocate. "Review of Proceedings of General Military Court in the Case of United States vs. Martin Weiss et.al." (PDF). Retrieved 16 September 2015.("US v. Weiss")

- The United Nations War Crimes Commission (1949). Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, vol. XI (PDF). His Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 16 September 2015. ("UN War Crimes Commission")

External links

- Concentration Camp Dachau: Special Orders 1933. Harvard Law School Nuremberg Trials Project. 1947.

- 7th Army, U.S. (1945). Dachau. University of Wisconsin Digital Collection.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Anderson, Stuart (2008–2010). "Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial". Destination Munich.

- Video Footage showing the Liberation of Dachau

- Concentration camps of Nazi Germany: illustrated history on YouTube

- The short film A German is tried for murder [etc.] (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- "Communists to be interned in Dachau". The Guardian. 21 March 1933.

- "Dachau in the First Days of the Holocaust". The National Interest. 21 April 2015.

- Cramer, Douglas. "Dachau 1945: The Souls of All Are Aflame". Orthodoxy Today.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". Stiftung Bayerische Gedenkstätten, German. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- "Exhibition Texts of Dachau Camp Memorial" (PDF). Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, German and English. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Dachau Memorial Site, UCSB Department of History". Professor Harold Marcuse, PhD. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- Doyle, Chris (2009). "Dachau (Konzentrationslager Dachau): An Overview". Never Again! Online Holocaust Memorial.

- Perez, R.H. (2002). "Dachau Concentration Camp – Liberation: A Documentary – U.S. Massacre of Waffen SS – April 29, 1945". Humanitas International. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "The European Holocaust Memorial". Landsberg im 20. Jahrhundert.

- Watson, Simon (Fall 2007). "Dachau Awakening". Queen's Quarterly 114/3. hdl:1807/72034.

- Dachau camp prisoner testimonies page, 041940.pl

- "The Angel of Dachau". – Pope Francis declares concentration camp priest a martyr – CNA

- "Traces of Evil". Illustrative History of Dachau and Environs

- Chrisinger, David (4 September 2020). "A Secret Diary Chronicled the 'Satanic World' That Was Dachau". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Dachau concentration camp

- Buildings and structures in Dachau (district)

- Tourist attractions in Munich

- 1933 establishments in Germany

- Tourist attractions in Bavaria

- World War II museums in Germany

- World War II sites in Germany

- World War II memorials in Germany

- Museums in Bavaria

- Medical experimentation on prisoners of war