Paracosm

A paracosm is a detailed imaginary world thought generally to originate in childhood. The creator of a paracosm has a complex and deeply felt relationship with this subjective universe, which may incorporate real-world or imaginary characters and conventions. Commonly having its own geography, history, and language, it is an experience that is often developed during childhood and continues over a long period of time, months or even years, as a sophisticated reality that can last into adulthood.[1]

Origin and usage

[edit]The concept was first described by Robert Silvey, with later research by British psychiatrist Stephen A. MacKeith and British psychologist David Cohen. The term "paracosm" was coined by Ben Vincent, a participant in Silvey's 1976 study and a self-professed paracosmist.[2][3][4]

Psychiatrists Delmont Morrison and Shirley Morrison mention paracosms and "paracosmic fantasy" in their book Memories of Loss and Dreams of Perfection, in the context of people who have suffered the death of a loved one or some other tragedy in childhood. For such people, paracosms function as a way of processing and understanding their early loss.[5] They cite J. M. Barrie, Isak Dinesen and Emily Brontë as examples of people who created paracosms after the deaths of family members.

Marjorie Taylor is another child development psychologist who explores paracosms as part of a study on imaginary friends.[6] In Adam Gopnik's essay, "Bumping Into Mr. Ravioli", he consults his sister, a child psychologist, about his three-year-old daughter's imaginary friend. He is introduced to Taylor's ideas and told that children invent paracosms as a way of orienting themselves in reality.[7] Similarly, creativity scholar Michele Root-Bernstein discusses her daughter's invention of an imaginary world, one that lasted for over a decade, in the 2014 book, Inventing Imaginary Worlds: From Childhood Play to Adult Creativity.[8]

Paracosms are also mentioned in articles about types of childhood creativity and problem-solving. Some scholars believe paracosm play indicates high intelligence. A Michigan State University study undertaken by Root-Bernstein revealed that many MacArthur Fellows Program recipients had paracosms as children, thus engaging in what she calls worldplay. Sampled MacArthur Fellows were twice as likely to have engaged in childhood worldplay as MSU undergraduates. They were also significantly more likely than MSU students to recognize aspects of worldplay in their adult professional work.[9] Paracosm play is recognized as one of the indicators of a high level of creativity, which educators now realize is as important as intelligence.[10]

In an article in the International Handbook on Giftedness, Root-Bernstein writes about paracosm play in childhood as an indicator of considerable creative potential, which may "supplement objective measures of intellectual giftedness ... as well as subjective measures of superior technical talent."[11] There is a chapter on paracosm play in the 2013 textbook Children, Childhood and Cultural Heritage, written by Christine Alexander. She sees it, along with independent writing, as attempts by children to create agency for themselves.[4]

Paracosms are one of the subjects of interest to the emerging field of literary juvenilia, studying the childhood writings of well-known and lesser-known authors. Joetta Harty in her essay "Imagining the Nation, Imagining an Empire: A Tour of Nineteenth-Century British Paracosms" contextualizes the paracosms of 19th-century British children, including the Brontë family, Thomas De Quincey's Gombroon and Hartley Coleridge's Ejuxria, with then-current events. Nike Sulway in "'A Date with Barbara': Paracosms of the Self in Biographies of Barbara Newhall Follett" explores adult reaction to children perceived as prodigies or geniuses, focusing on how their biographies often focus on their imaginations and paracosmic creations rather than on their daily lives, citing as an example adult reactions to child author Barbara Newhall Follett.[12][13] In Virtual Play and the Victorian Novel, Timothy Gao focuses on "paracosmic play or worldplay" on the part of De Quincey, Coleridge, Charlotte Brontë, Anna Jameson, Thomas Malkin and Anthony Trollope.[14]

Examples

[edit]

Examples of paracosms include:

- The world of Pandora in the science fiction epic Avatar was first dreamed of by James Cameron in his early teens and added to over the course of his life. Not until the technology was possible in the late 2000s did he finally start production on it.

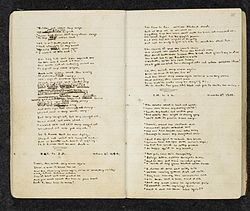

- Gondal, Angria, and Gaaldine, the fantasy kingdoms created and written about in childhood by Emily, Anne, and Charlotte Brontë, and their brother Branwell, and maintained well into adulthood. These kingdoms are specifically referred to as paracosms in several academic works.[1][15][16][17][18][19]

- Pamela Russell, Head of Education and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Programs for the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, specifically uses the word "paracosm" in describing the imaginary world created by Goshen, New Hampshire teens Walter, Arthur and Elmer Nelson in the 1890s and chronicled in a collection of miniature books.[20][21]

- K.C. Remington has written over twenty books in the Webbster and Button Children's Stories series, set in a paracosm called the Big Green Woods.[22]

- Hartley Coleridge created and maintained the land of Ejuxria all his life.[23]

- Austin Tappan Wright's Islandia began as a childhood paracosm.

- M. A. R. Barker began developing Tékumel at age ten.

- Ed Greenwood (born 1959) began writing stories about the Forgotten Realms as a child, starting around 1967; they were his "dream space for swords and sorcery stories".[24]

- Borovnia, the fantasy kingdom created by Juliet Hulme and Pauline Parker in their mid-teens, as portrayed in the film Heavenly Creatures.[25]

- The modern fantasy author Steph Swainston's world of the Fourlands originated as an early childhood paracosm.[26]

- Henry Darger began writing about the Realms of the Unreal in his late teens and continued to write and illustrate it for decades.

- Joanne Greenberg created a paracosm called Iria as a young girl, and described it to Frieda Fromm-Reichmann while hospitalized at Chestnut Lodge. Fromm-Reichmann wrote about it in an article for the American Journal of Psychiatry;[27] Greenberg wrote about it as the Kingdom of Yr in her novel I Never Promised You a Rose Garden.[28]

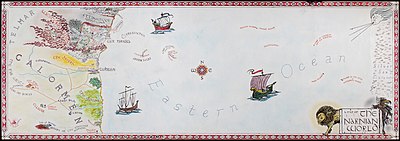

- As children, novelist C. S. Lewis and his brother Warren together created a paracosm called Boxen which was, in turn, a combination of their respective private paracosms Animal-Land and India. Lewis later drew upon Animal-Land to create the fantasy land of Narnia, the setting of The Chronicles of Narnia.[29]

- The documentary film Marwencol centres on an imaginary town created by artist Mark Hogancamp as a kind of therapy for trauma and brain injury brought about by a violent assault.

- Artist Renaldo Kuhler invented a fictional country called Rocaterrania as a teenager, and continued creating and illustrating it for the rest of his life.

- Additional paracosmists are listed in Michele Root-Bernstein's[who?] Inventing Imaginary Worlds: From Childhood Play to Adult Creativity Across the Arts and Sciences in 2014, and on the related website, Inventing Imaginary Worlds.[importance?][30]

See also

[edit]- Fantasy-prone personality – Disposition toward strong fantasies

- Fantasy (psychology) – Mental faculty of drawing imagination and desire in the human brain

- Fantasy world – Imaginary world created for fictional media

- Fictional universe – Self-consistent fictional setting with elements that may differ from the real world

- Hyperphantasia – Condition of having extremely vivid mental imagery

- Imagination – Creative ability

- Maladaptive daydreaming – Trait associated with some mental disorders

- Method of loci – Memory techniques adopted in ancient Roman and Greek rhetorical treatises

- Subcreation – Narrative genre in modern literature and film

- Worldbuilding – Process of constructing an imaginary world

References

[edit]- ^ a b Petrella, Kristin (2009-05-01). "A Crucial Juncture: The Paracosmic Approach to the Private Worlds of Lewis Carroll and the Brontës". Surface, Syracuse University Honors Program, Spring. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-15.

- ^ Morrison, Delmont C., ed. (1998). "The Paracosm: a special form of fantasy". Organizing Early Experience: Imagination and cognition in Childhood. New York: Baywood.

- ^ Cohen, David; MacKeith, Stephen (1992). The Development of Imagination: The Private Worlds of Childhood. Concepts in Developmental Psychology. Routledge.

- ^ a b Alexander, Christine (2013). "Playing the author: children's creative writing, paracosms and the construction of family magazines". In Darian-Smith, Kate; Pascoe, Carla (eds.). Children, Childhood and Cultural Heritage. Routledge.

- ^ Morrison, Delmont C.; Morrison, Shirley L. (2005). Memories of Loss and Dreams of Perfection: Unsuccessful Childhood Grieving and Adult Creativity. Baywood. ISBN 0-89503-309-7.

- ^ Taylor, Marjorie (2001). Imaginary Companions and the Children Who Create Them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514629-8.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam (2003). "Bumping Into Mr. Ravioli: A Theory of Busyness, and Its Hero". In The American Society of Magazine Editors (ed.). The Best American Magazine Writing 2003. Harper Perennial. p. 251.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) Originally appeared in The New Yorker on September 30, 2002, and also found in Gopnik's collection of autobiographical essays, Through the Children's Gate: A Home in New York. Vintage Canada, 2007. ISBN 1-4000-7575-0. - ^ Root-Bernstein, Michele (2014). Inventing Imaginary Worlds: From Childhood Play to Adult Creativity Across the Arts and Sciences. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4758-0979-4.

- ^ Root-Bernstein, M. & Root-Bernstein, R. (2006). "Imaginary Worldplay in Childhood and Maturity and Its Impact on Adult Creativity". Creativity Research Journal, 18(4): 405–425.

- ^ Po Bronson and Ashley Merrin (10 July 2010). "The Creativity Crisis". Archived 2010-08-21 at the Wayback Machine. Newsweek. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Root-Bernstein, Michele (2009). "Imaginary Worldplay as an Indicator of Creative Giftedness". In Larissa Shavinina, ed. International Handbook on Giftedness. Springer.

- ^ Nike Sulway, "'A Date with Barbara: Paracosms of the Self in Biographies of Barbara Newhall Follett". In Dallas John Baker, Donna Lee Brien and Nike Sulway, eds., Recovering History through Fact and Fiction: Forgotten Lives. Cambridge Scholars, 2017.

- ^ David Owen and Lesley Peterson, eds. (2016). Home and Away: The Place of the Child Writer. Cambridge Scholars.

- ^ Timothy Gao (April 2021). Virtual Play and the Victorian Novel: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Fictional Experience. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Diane Long Hoeveler, Deborah Denenholz Morse, eds., A Companion to the Brontës. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- ^ Emily Brontë, Gondal Poems. 1973 by Folcroft Library Editions.

- ^ Emily Brontë, Gondal's Queen, A Novel in Verse. Edited by Fannie Ratchford. University of Texas Press, 1955.

- ^ Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford, Legends of Angria. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933.

- ^ Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford, The Brontes' Web of Childhood. Columbia University Press, 1941.

- ^ Rebecca Onion. Archives of Childhood: The Worlds and Works of the Nelson Brothers. Archived 2016-04-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Boyhood". Archived 2016-07-15 at the Wayback Machine. Slate, 28 May 2015.

- ^ K.C. Remington Archived 2018-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, profile at Smashwords e-book site, with a bibliography.

- ^ Andrew Keanie, Hartley Coleridge: A Reassessment of His Life and Work. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Winter, Steve; Greenwood, Ed; Grubb, Jeff. 30 Years of Adventure: A Celebration of Dungeons & Dragons, pages 74–87. (Wizards of the Coast, 2004).

- ^ "The Fourth World". Archived 2017-07-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Dangerous Offspring: An Interview with Steph Swainston". Archived 2014-02-25 at the Wayback Machine. Clarkesworld Magazine. October 2007.

- ^ Fromm-Reichmann, Frieda (December 1954). "Psychotherapy of Schizophrenia". American Journal of Psychiatry 111:410–418.

- ^ Greenberg, Joanne, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. ISBN 0-8124-1588-4.

- ^ Lewis, Clive Staples (1956). Surprised By Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-687011-8.

- ^ Presley, Ed. "Inventing Imaginary Worlds". Inventing Imaginary Worlds.

External links

[edit]- Francis Jacox, Ejuxria and Gombroon: Glimpses of Day-Dreamland. 1871 essay discusses many paracosms created by people who later became writers, although he never uses the word.

- Elizabeth Knox, Origins, Authority, and Imaginary Games discusses the creative process as paracosms evolve into adulthood.

- Sarah Knox, Identity, Inclination and Imaginary Games is a response to Elizabeth's essay.